I’ve had the blessing of going to see a number of theater productions over the last couple of weeks. One of the perks of living in London, one that I don’t take for granted, is being able to see loads of live performance arts. Any and every day of the week you can pick and choose between tens, sometimes hundreds of live shows, comedy, theatre, music - you name it, it’s on offer.

I didn’t grow up doing arty things like ‘going to the theater’. My first theater outing was sometime in the 2010s, to see a strange ol’ thing called ‘Avenue Q’. My dear friend Avrithi and I were university students (or perhaps we had just graduated, I cannot remember), and thought it would be ever so adult of us to go ‘to a show’.

Honestly, I had no idea what was happening on stage. I think I spent half of the show being like…is this okay? Here’s a sample to give you a sense:

I didn’t go to the theater for quite a few years after that!

But, fast forward a decade or so, and how things have changed! I’ve written for the theatre, had plays produced, and yes, have become someone who enjoys a cheeky night out on the West End. Alhamdulilah.

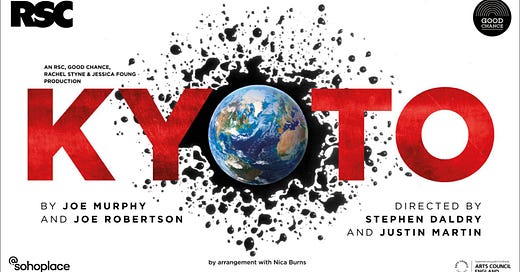

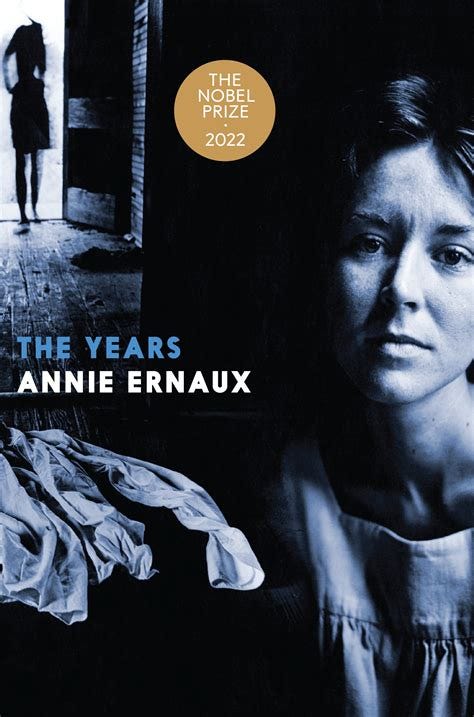

All that to say, I recently saw two shows that I’ve been mulling on and have wanted to share with y’all: The Years, and Kyoto.

An adaptation of the book Les Années by Nobel prize winner Annie Ernaux, The Years was a clever production of a complex book. An autobiography of sorts (I must confess, one I have yet to read) it is the story of a woman’s life in France, of a tale as old as time: the process of aging, of realising that no matter what you do, time will march on.

The book has been described as a ‘collective autobiography’, but watching the play, I was struck by how the collective was being defined. ‘Algeria’, ‘The Muslims’, ‘The Arabs’, etc, were all referred to obliquely, described as outside the group knowingly understood as ‘us’, ‘we’. The play reminded me that in Ernaux’s world, in the world of the play, the critics, the reviewers - people like myself are Other. We are subjects, more news than human, more history than present, more margin than main text. Even if I watched, and like everyone else, thought of myself as the protagonist, the show made it clear that this narrator was not talking about me.

The dissonance was discomfitting. I could not escape the reminder that while I may imagine myself as part of such a collective experience, I was performing the imaginative leap those in the dominant culture rarely take themselves1.

Despite my sense of Othering, one aspect of the play rang universally true. A line about sitting at the family dinner table. That moment when you look around and realise there are children and nieces and nephews and many younger than you, while your parents were now the elders; most, if not all of the older generation having died.

Shit, I thought. I’m the middle now. I’m in the middle generation. How did that happen? What does that mean?

There is still a sense of a ‘future’, but it’s not as shiny and untouched as it was a decade ago. There is less sense of mystery. Inroads have been made, choices settled upon. We are in the future we once dreamed about. We are the adults in the room.

Subhanallah.

I left that play feeling worried. Not about the world, but about my place in it. How do I handle this ever rushing passage of time? How do any of us?

But the next play I saw placed me in an entirely different headspace, though I feel like the two are in conversation.

Kyoto is pitched as a ‘political thriller’, but it is more historical drama. It is about how, against all odds, the Kyoto Protocol was passed. You mightn’t think there’s much in it, but I’m tellin ya. It was a ride!

I didn’t know much of the Protocol’s history. Frankly, by the time I came to political consciousness around the climate crisis, I had taken Kyoto for granted. But this was a fascinating, and unexpectedly inspiring, take on a diplomatic process that feels ever more extraodinary in these times. How did they get all the countries to agree?

The negotiations were fraught. Backbreaking. Went throughhhh the nights. Look at the timestamp in the video below: they worked past sunrise on the final day.

We know of course, that the Protocol did not quite achieve what it set out to do. But there was something about the characterisation of the Chairman of the negotiations, Raúl Estrada, that moved me. On stage, when faced with oil lobbyist Don Pearlman - obsessed with winning ‘For America’ at all costs2 - the typically humerous Raúl’s is earnest, deadpan in response.

I will show you what I’m fighting for, he says to Pearlman. Agreement.

It’s hard, isn’t it?

Agreement.

It’s bone-crushingly hard.

That’s what struck me as I watched the dramatised negotiations of the Protocol, and has remained with me since. I wonder about the people who were there, trying their best, and those who ultimately managed to achieve what few had done before, or since. Agree. On doing something. On action. On progress. On change, for the better. The feat, they pulled off. What a feat! Yes, we can say things haven’t panned out as they might have hoped. But they showed us what was possible, did they not? The world is surely better with the Protocol than without it?

It’s so much easier not to agree. It’s so much easier to poke holes, to find flaws, to decide against, to advocate for the bleeding devil. It is functionally and objectively easier to destroy than it is to build. That is why the work so many of us do is so hard - because we want to create. Alternatives. Possibilities. Futures.

But in order to do so, we have to find ways to agree. We have to find zones of agreement - what we can, at the bare minimum, come together on.

It was curious, to watch negotiations being made. It became clear that this wasn’t about the moral positions of the delegates - that wasn’t what was on the table. Everyone understood there were a variety of moral and political positions, took that as a given. No, negotiations were about something else.

They were about asking the question: if we acknowledge the urge to begin from a place of self interest, how do we get everyone - everyone - to shift to the collective?

How do we get more people on board?

How do we get people on side?

What is the possibility?

What is the negotiation?

What is the compromise?

What is in the zone of agreement?

Now, I don’t know if we can take the dramatisation of a UN diplomatic negotiation as gospel, but there’s something in it for me. Something in understanding that engaging with ‘opposing’ parties from a place of refusing to surrender might be morally soothing, but won’t get us anywhere. Now of course, not all noegotiations are in good faith - most of Don Pearlman’s work was in terrible faith, that man was dripping poison from the get go! But if we’re all working towards the same goal? Surely there’s gotta be a way.

Heck, what am I talking about. I’m not negotiating anything right now. Why did this have such an impact?

Maybe this isn’t a piece about collective action, or individual memory. Maybe it’s about the power of art. About the power of a story to move us. To shift something. To change the world.

Did you know that Kyoto, the city, was almost destroyed by the atomic bomb in World War Two? Apparently, it was taken off the list by Secretary of War Henry Stimson. According to some historians, because he’d honeymooned there.

Instead, the US bombed Nagasaki.

Not all our decisions are going to be as world defining as Stimson’s, or Estrada’s. But they matter. Because what is society, but the collective choices we all make? What is culture, but the ordinary things we do, every day?

Has there been a piece of art that’s moved you? Have you shifted into the zone of agreement recently? Would love to hear from you, friends.

Blessings,

Yassmin

But I cannot judge Ernaux’s work, as I have not read it. I reflect only on my experience with the play.

i.e. destroying any chance for agreement on climate change

A beautifully written piece that elegantly describes how the themes of three different theatre plays come together around racism and consensus building. Then Yassmin leaves us with a question to ask ourselves how each of us experiences collective agreements? I certainly experience this in my marriage and with family and use this collective view as a guide in how to make the right choices.

Thanks for the your thoughts. As an Australian in London I was wondering what I should see and couldn’t abide a musical. Kyoto sounds well worth the visit.