Almost ten years ago, I was on a visit to Uganda as part of my introduction to the board of Childfund Australia. From Kampala we drove to the northern city of Gulu, before embarking on a tour through surrounding villages, meeting local partners and observing the charity’s work on the ground. The landscape was vibrant, lush, viridian green on ocher. It seemed peaceful, to my foreign eyes. Until I began to ask questions, pay attention, to remember.

Remember Kony 2012? That weird-ass viral video where the white American filmmaker Jason Russell campaigned for the arrest of Ugandan militant Joseph Kony? Perhaps, like many around the world, that was your first time learning of the man. This area of Uganda was Kony’s deadly playground. According to the UN, Kony along with his ‘Lord’s Resistance Army’, killed more than 100,000 people and displaced more than two million. UNICEF reports that ‘from 1987 to 2006, the armed group abducted more than 20,000 children to use as soldiers, servants or sex slaves.’

As we drove, our driver shared rough sketches of his own memories from that time. Hiding in churches, though nowhere was not safe. Children forced to murder their own parents, dismember their siblings, horrifying tales of dehumanisation meted out by soldiers who were children themselves. His tone was matter of fact. I could not imagine the horror.

He pointed out memorials that were erected here and there, but there seemed so few. I could not help but compare them to the monuments for those lost in European battles, those who are commemorated in grand installations across the world, entire museums raised in their names. Here, no matter how gruesome your death, or what you had to do to survive it, who would remember your name?

I tried to imagine. The crushing fear of being hunted, its dark, haunting isolation. The despair, knowing in your bones that nobody is coming to save you, and if - when you died here, nobody would even remember your name.

Even in death, injustice continues.

Memory matters, if not for the dead, then for the living. There is a violence in the invisibilising of atrocity, one that rips dignity away from all those affected. It says this terror is normal, this is part of who you are, this is all you deserve. It leaves no space for grief, mourning, reflection. It is inhumane, inhuman.

I began this newsletter with the intention of only writing about the Mullivaikkal massacre, which occurred on the 18th of May, 2009 and marked the official end of the brutal war in Sri Lanka. In the course of reading about northern Uganda however, I learnt about the Lukodi massacre, marking its 20th anniversary today. It feels remiss not to mention that on the 19th of May 2004, as detailed in this Justice and Reconciliation report, the ‘Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) raided the village of Lukodi, and carried out a massacre that led to the death of over sixty people.’

I urge you to read the paper, which was a response to community leaders wanting to document their experiences ‘for purposes of acknowledgment and preserving memory.’ The report considers the ‘development and implementation of a community model of reconciliation,’ and it’s one of the most powerful reports I’ve read: detailing the experiences of massacre, in order to try move through, and on.

How survivors can have the capacity to turn their trauma into wisdom is for me, forever a source of awe.

Now, let us turn to Mullivaikkal.

Aran Mylvaganam, founder of the Tamil Refugee Council, writes movingly about his experience as a Tamil person born during the genocidal war. The conflict was close to home; his school was bombed by the Sri Lanka Air Force in the mid-90s, incidentally by an Israeli supplied plane. His brother and cousins were killed. In a piece published yesterday, titled ‘The Forgotten Genocide’, Mylvaganam takes us through a brief history of the Sri Lankan civil war, before turning to focus on Mullivaikkal.

‘The government designated a series of “no fire zones”, where people were told to flee to avoid the bombing,’ he writes, of which Mullivaikkal was one.

Once assembled, they were massacred. More than 300,000 Tamils were trapped, and according to census records, at least 146,000 went unaccounted for when the assault subsided. The Sri Lankan army systematically targeted Tamil civilians, leading to one of the most horrific genocides in recent history.

At a memorial event held by Amnesty International this week, Agnès Callamard, Secretary General at Amnesty International, said:

“Ahead of this event, we have witnessed clampdown on the memory initiatives, including arrests, arbitrary detentions and deliberately skewed interpretations of the Tamil community’s attempts to remember their people lost to the war. Authorities must respect the space for victims to grieve, memorialise their loved ones and respect their right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.”

It is worth remembering that memory is not only about healing, it is about justice.

Cast your mind back to 2009. Do you remember hearing about this massacre? People spoke of Sri Lanka mostly as a beautiful tourist destination, from what I recall. ‘As European tourists sunned themselves on Sri Lanka's southern beaches in 2009,’ said this BBC report from 2012, at the other end of the island Tamil people cowered as ‘scores of rockets from multi-barrelled launchers pummelled the area.’

News reports from the time announcing the end of the war barely mentioned Mullivaikkal, certainly, the scale of the atrocity was yet to be realised. Some reports from the era claimed ‘40,000 people’ were killed during the three-decade conflict, this BBC report said it was at least ‘100,000’. Yet we now know that the death toll in one place - Mullivaikkal - was more than both those numbers combined. Will we ever have a complete account of all those lost?

‘The intimidation, surveillance and harassment of Tamil war survivors continue,’ writes journalist Nirmanusan Balasundaram in Aljazeera. ‘The Tamil community is still denied the right to collective remembrance of the dead under false claims that such an act would endanger national security.’

Remembering can be an act of resistance.

Who has control of the story?

Who has control of the story has control.

Who has control of the story has control of the memory.

Who has control of the memory has control.

It is worth remembering that memory is not only about the past. Memory defines our present, creates our future.

Who gets to remember?

This week, I think of Ludoki, I think of Mullivaikkal, I think of the Palestinian Nakba. I think of Darfur, I think of El-Fasher, I think of all those who I do not know yet to remember, but I hope to one day, inshallah. May we always bear witness.

Lest we forget.

Watch: No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lanka

I must warn you, this is an extremely harrowing watch. The documentary looks at the final days of the war, through personal stories and video from the field, including ‘by the perpetrators themselves.’ It also details the failure of the international community to do anything to stop the massacre. When you hear ‘safe zones’ in relation to Palestine, know this exact language was used 15 years ago in Mullivaikkal. El-Fasher in Darfur today is also facing a similar catastrophe.

Listen: Eelam Songs

‘Eelam’ is the Tamil name for the land known as ‘Sri Lanka’. Eelam Liberation songs make up an entire genre, but I’m sharing below one I came across titled ‘Mullivaikkal’. If you know recommend any other Eelam songs, please let me know in the comments!

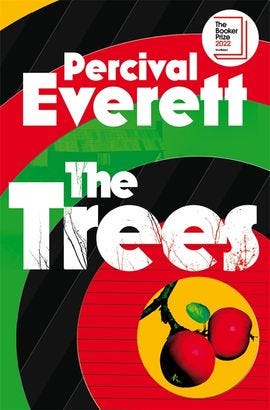

Read: The Trees

My final recommendation is a complete tonal shift. It again, considers memory and atrocity, but through the dark, satirical humour of author Percival Everett, rapidly becoming one of my favourite fiction writers working today. ‘Part police procedural, part black comedy, the novel is both irreverently silly and deadly serious,’ said the Literary Review. Here’s the blurb: “When a pair of detectives from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation arrive in Money, Mississippi, to investigate a series of brutal murders, they find at each crime scene an unexpected second body: that of a man who resembles Emmett Till.” Everywhere you expect this book to go, it does not. Enjoy…

Thanks, as always, for your attention, your comments and your support. I know today’s newsletter was heavy, and so thank you also for sitting through the painful process of remembering, of bearing witness, of holding space.

I invite you to - in this moment - close your eyes and take three, deep, belly breaths. Unclench your jaw, lower your shoulders, and breathe.

Until next week, inshallah.

Yassmin

Thank you again Yassmin, for another thought provoking and challenging post. I enjoy your crital analysis of issues - ‘enjoy’, might be strong a word as sometimes they poke me in places that confront my biases! But, I also thank you for that too; it is good to have our biases poked!😄 I love your writting and enjoy your crafting of the words and images.

I always wait until I am sitting on the train after a days at work, I read your post- do I can savour the concepts….look out the window.….pondir your thoughts.…. and reflect on its impact on me.

You are valued, seen and appreciated. Thank you. 💜