With the news coming out of El Fasher this week of massacres so horrific the blood is visible from space, many folks have recently woken up to the terrors folks in Darfur and across Sudan have been facing for months now. As a regular reader of this newsletter, you are likely familiar with my writing on current war against civilians, whether on the battle of narrative, the heartbreak of not being seen, the struggle with powerlessness. I didn’t want to repeat the same sentiments, regurgitate familiar despairs. Today, I instead share a different piece, one I originally wrote for and published with the Oxford Academic journal ‘Communication, Culture and Critique’. It is a piece inspired by Binyavanga Wainaina’s “How to Write About Africa” published in Granta twenty years ago.

As you read this short piece, remember what I write in the abstract: “this article’s role is not to scold. It is a balm for Sudanese readers, African readers, those who recognize the invisibilizing that Sudan and the Sudanese have been subjected to, in this decade and the preceding. It is a release, a reaction, and an invitation: what might it really mean, to write about Sudan?”

Always use the word “forgotten” in your title. Subtitles may include words like “hopeless,” “violent,” “crisis,” “conflict.” Other words that might be useful are “ignored,” “invisible,” “neglected.” Remember to use the passive voice. Do not draw attention to who is doing the ignoring or forgetting, only imply that this is the permanent and unchanging curse of the state.

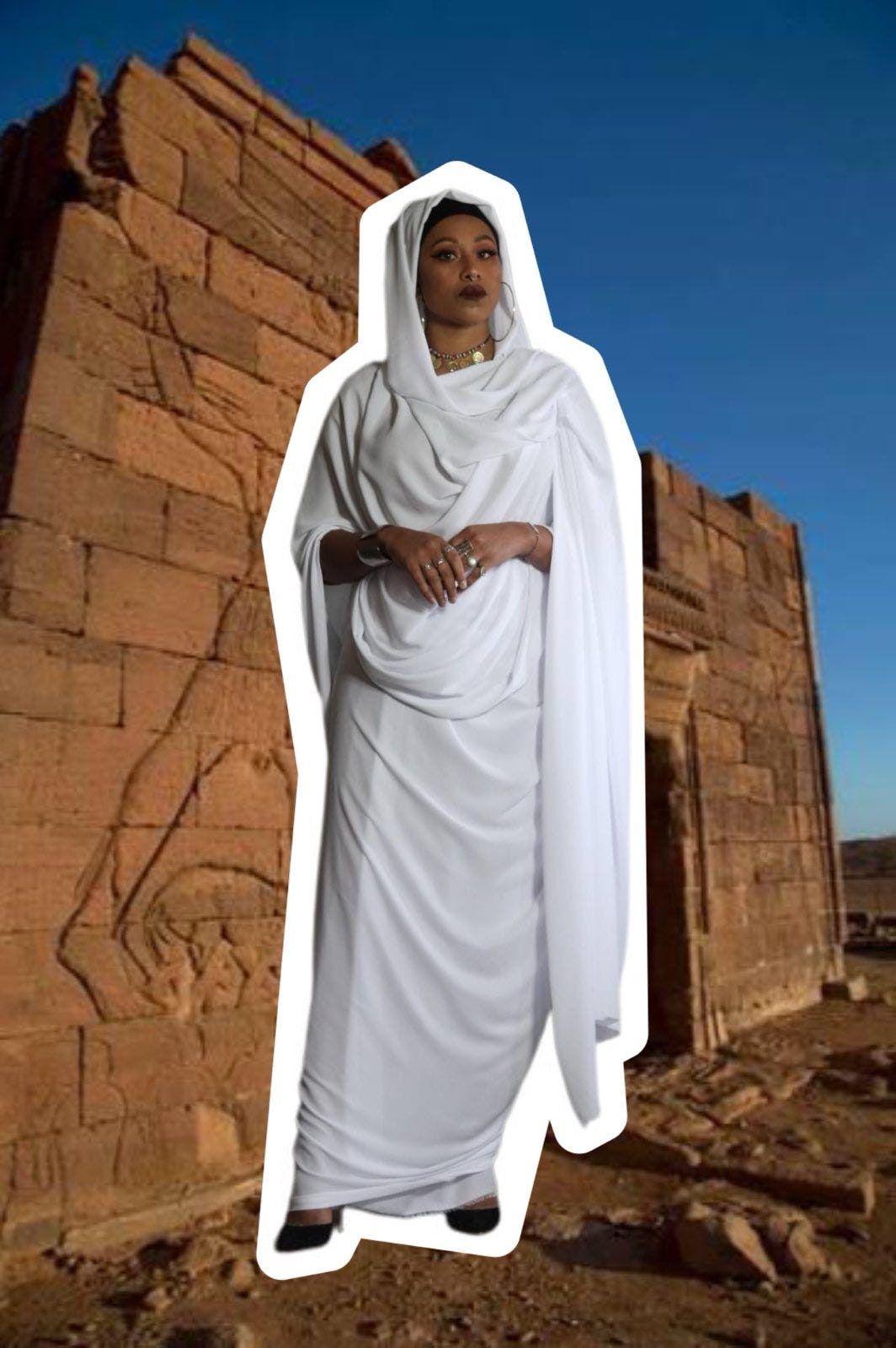

Never include an image of the natural beauty of Sudan or Sudanese people in your work. Ensure desperation bleeds through the pages, through protruding bones, bulging bellies, blackened and bombed out carcasses of buildings. Think in sepia. If you want to be particularly striking, use a close up shot of a woman’s eyes, staring down the barrel of the camera, her entire face wrapped up in bright cloth, an air of defiance and accusation in her gaze. A fly perched on the skin like a mole is good. The objective of any image is to induce pity, or guilt.

In your article, in your opinion piece, in your Pulitzer Prize-winning feature, treat Sudan as if it were one homogenous place. Sudan is made up of 18 states, 50 million people and over 70 indigenous languages. Ignore this. Speak of “the land,” whisper in awe at the vastness of the desert, decry the harshness of the conditions. Refer to geographies more often than cities; mention “The Sahel,” “The Sahara,” “The Horn,” “The Red Sea” instead of “Atbara,” “El-Obeid,” “Nyala,” “Sennar”. Describe Sudan using other countries people have heard of but also do not understand. Call it “the new Somalia,” “the new Syria,” “the new Libya,” “the new Yemen”. Don’t worry too much that these framings are inaccurate and do not make sense. Focus on the unintelligibility, the mass suffering, the vibe. Suffering is a language people in your world can understand, but don’t forget to make clear that this is the type of catastrophe unique to “the region,” that is to say, a situation so “deplorable,” so “inhumane,” that it could not possibly happen “here,” wherever your Western audience might be.

Describe what is happening as a “civil war.” The audience will be most comfortable when the Sudanese are seen to be killing each other like unthinking savages, rather than for common reasons like territorial and resource acquisition, the gain of political and economic power. If you mention “genocide,” intimate the reasons are about “tribal tensions” or “rivalries,” or even better, “hatred”. Emphasize the lack of thinking (in them, not you). You may choose to describe it as a “proxy” war, suggesting an understanding of the geopolitical ramifications of the situation. Resist the urge to delve into specifics, these are irrelevant and boring to your reader. Avoid using the most accurate phrase, “counter-revolutionary” war. It has far too many syllables and brings to mind the Sudanese civilians who successfully overthrew a dictator of almost thirty years in a powerful and non-violent resistance movement. Don’t mention the revolution at all. Your readers cannot imagine learning about community building, mutual aid and justice from the likes of Sudanese people. The only knowledge they will accept from Africans must be veiled in dust, shadowed by witchcraft, involve some beating of the earth or ingesting offal-like food.

Taboo subjects: moments of ordinary domestic joy, students going to school, laptops and any form of technology that feels current (like an Apple watch), parts of the country not experiencing direct conflict where life has continued uninterrupted, humor. Sophisticated art and culture.

Speak of Sudan as a place with no history and no future. Ignore the ancient Nubian pyramids in Nuri, Jebel Barkal, El-Kurru, Meroë, but if you do mention them, don’t forget to describe them as forgotten. In order not to confuse your audience, ensure you give all credit to the Egyptians for any “civilization” that Sudan may unexpectedly contain. Remember, Sudan is the gateway to “real” Africa, and by “real,” you mean “Black.” Make sure to transpose North American understandings of racial hierarchies here. Yours is the superior understanding.

Remind readers at the beginning that this is the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, and state it as natural fact, rather than the result of a series of choices made by leaders and institutions your readers admire. Emphasize the severity of the crisis but avoid using testimony from Sudanese people themselves. Use data collected by organizations your readers believe and respect, even in a post-fact world. Two to three letter institutions are best: the UN, WFP, AI, IMF, RC, MSF. Spend most of your time covering the basic facts but add no context, so it appears that the conflict erupted apropos of nothing, that this is simply a return to the natural state of the Sudanese people. Use Sudan and Africa interchangeably in your text, your readers/viewers/consumers will not notice the swap. Render Sudan as Africa, and Africa as Sudan.

Don’t trouble yourself with precision, accuracy and analysis. Ensure you make broad, sweeping statements about the evil rife within the military elite and militiamen you encounter, either in person, or virtually, or on your social media feed. Mention foreign interests, but do not single out the American dollars, British Pounds, Euros, Riyals or Dirhams that are complicit. Just encourage a boycott, obliquely. Do not explain the strategy. Sudan does not need strategy. It needs attention.

When you speak to Sudanese people, make sure to ask them why “everyone” forgets about the war in Sudan. Ignore the fact that they themselves have been advocating, have been donating, have been screaming about it from the rooftops since the first bullets were fired (make sure you mention the bullets being fired, ideally during your interview, even if it is being conducted virtually and you are thousands of miles away). Presume this Sudanese person has not tried hard enough to tell the world about the war, a war that you know is so very terrible and that you pride yourself on educating “the world” about. Offer suggestions for how they can “get the word out,” as you have done. You love Sudan, you love Africa: your words, your platform is evidence of how much you care. Your liberal credentials are impeccable.

Once you have done your bit, published your article or your post, send it to every single African you know, as a demonstration of your connection to the cause. Take pride in the fact that you are not like other Westerners, you do care, you are not racist, you are different. Consider your reposts about Sudan proof that you are not anti-black. Do not feel bad when you mix up the Sudanese flag and the Palestinian one. Decide to wear them both, that way you are protected from any critique.

When you win a prize for your work “raising awareness,” make sure to thank your Sudanese “partners” in your acceptance speech. They might have been the journalists on the ground risking life and limb to procure the information, but that is not what is important. Your platform is. You are the conduit through which news about Sudan arrives. This is vital work, and you do it because you care. When you accept the award, do not mention that your Sudanese partners were unable to get a visa to enter the country where the ceremony is being held.

We don’t know how many people have been killed in El Fasher. If you want to donate to directly support folks on the ground who have escaped, consider Sudan Solidarity Collective.

A family relation who volunteers with the SSC told me recently how their contacts in community kitchens in El Fasher were updating the group chats as they escaped the town… and as soon as they arrived to a safe place (like Tawila) they were immediately writing about setting up new kitchens, the logistics of how to feed and care for everyone else. Imagine! You’ve just escaped a massacre, and as soon as you’re safe, you begin to think about how to look after each other? The examples of mutual aid and support Sudanese people and the people of Darfur demonstrate is utterly inspiring.

So. I continue to share information and links on my instagram, and will be posting shortly about a fundraising auction that will go live in a couple of weeks, inshallah. Stay tuned, do not despair, and keep talking about Sudan. It’s the least we can do.

Until next week, inshallah.

Yassmin

Boycott UAE, sanction UAE, for driving and enabling this genocide of Sudanese families.

Yassmin, thank you for all the educational content you post and the Sudanese organisations we can help. Reading this article again reminded me why we are fighting for a better world. No more murderous capitalism (and its fellow colonialism) that ends up in genocide when people don't comply with the plunder and erasure of their lands and cultures (resisting is the most understandable answer to this theft and killing). Doing everything we can in the Global North to stop this genocide, helping Sudanese people live and reconstruct their beautiful country themselves and learning more about the rich history and culture of Sudan 🇸🇩🙏🏻💚