48 BC

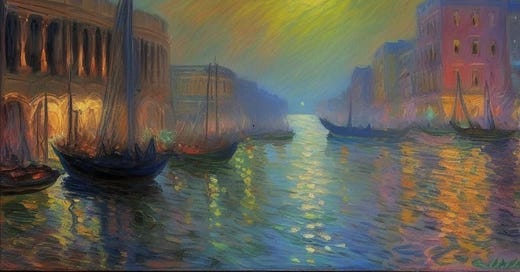

Alexandria’s eastern harbour held three silences.

Alexandria was a vibrant city, perched on the coast of the Mediterranean sea, proud and unpredictable. The royal lighthouse stood like a sentry just off the shore on the island of Pharos, a four-hundred foot tall structure carved from limestone and marble, wrapped in sculptures of marble and bronze. From the top of the marvellous pillar, a keen eye could spy the rugged coasts of Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes, even Sicily. On a clear night, the blazing light of its fire was visible for hundreds of miles, illuminating the city’s nightly raucous revelry.

Basking in the warm glow, beneath the tower, lay the royal palace. The path to the vast complex from the center of the city was inlaid with marble and onyx, lined by Ionic columns, each topped with sweeping papyrus fronds. Visitors, like the rows of soldiers currently guarding the entrance, would walk underneath five separate archways, sharp and imposing, before reaching the front door, a three storey stone structure flanked by snarling Crocodile gods dressed in Roman finery. Behind these doors, through the grid-like structure of decadently decorated hallways and rooms, past the Roman sentries and scurrying servants, sat a man at a desk that was not his own. The man was Julius Caesar.

Tonight, there was no feast, no merriment of festivity. The city was quiet, as if captured in a painting, or carved into stone. The first silence was that of a city holding its breath.

Outside, on ship, swaddled in comfort behind a different set of soldiers, was another man. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to call him a boy, this Pharaoh of Egypt. Pharaoh was how his many advisers, particularly the sharp tongued, ambitious eunuch Pothinus, addressed him to his face. Ptolemy was the thirteenth boy in his family to bear this name, and while at fourteen years of age, he may have been considered merely a child, the children of the Ptolemaic family were no ordinary progeny. He had been married for four years, although the matrimony was not a happy one: the teenager had exiled the woman who was both his wife and sister. Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, whose name meant ‘Father-Loving God’, was short and chubby, with a weak chin and an impressionable mind. He understood the family he was born into, and feared his siblings, as all right-minded members of the royal family did. He wore a white ribbon around his head, tied neatly into a bow at the nape of his neck, and chewed incessantly on its trailing edge. He outsourced all his decision making to his regent. Despite his tender age, Ptolemy XIII had the ego of a man three times his age. It was a quality Pothinus encouraged, the regent understanding this was a lever by which to best control his charge.

Pothnius had encouraged Ptolemy to take his rhetoric tutor’s advice on how to woo their foreign occupier. ‘Dead men don’t bite,’ Theodotus had proclaimed, and so, Ptolemy sent a gift to the Roman in his palace. A severed head in a wicker basket, rust red blood matted in the deceased man’s hair.

The second silence was that of a young Pharaoh, waiting to hear the news.

In the same harbour, hidden in the folds of the palace’s silky shadow, bobbed another boat, small and discrete. Inside the boat sat two women, one with hands roughened by physical labour, the other’s with hands softened by concoctions of milk and honey. The women had travelled - one rowed, the other navigated, strategised, prayed - up the Nile for days, as soon as they had heard of the Roman entering the city. But the women were not completely alone. With them was a third, hidden from the eyes of all but one.

The third had answered the call to rise from her resting place in the Realm of the Dead, a request phrased as a demand, given the use of her Secret Name. The journey to one’s transfigured state was only for the worthy, a journey this Goddess had taken with ease. Nefertiti, a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, with a face carved as if from obsidian, dark-skinned and charmingly haughty, was with the two women now, as spirit, soul, a being unknown but not always unseen.

The second woman, Charmain, had been chosen for this particular voyage for her loyalty as much as for her prowess with the oar. The central figure on this boat, a slip of a woman who had only seen twenty-one summers, needed absolute, undying fealty. Exile from her kingdom had been harsh. With Rome’s civil war lapping up on Egypt’s shore, the banished Queen understood the Gods were preparing the land for battle. Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator, the direct descendant of Alexander the Great, a Macedonian Pharaoh with olive skin and a white ribbon tied around her jet black hair, knew that this was the moment. She needed to secure an audience with Caesar, if she was to have any chance of ruling her kingdom, of returning Egypt to even a shadow of its former glory. It was her birthright. But if she was seen, her brother and his regents would not hesitate to kill immediately, as was the way of the Ptolemies. She searched for another way in.

Nefertiti’s advice was simple.

Hide in plain sight.

Cleopatra readied herself.

The third silence was that of a woman preparing to die.

This is the prologue for a historical fiction novel I began a couple of years ago. I had never considered that I might enjoy writing historical fiction, despite loving the genre myself, however when the opportunity came up I found the words flowing like water through the Nile…

Hope you enjoyed this little excerpt, and sending best wishes for the rest of your weekend!

Best,

Yassmin