I’m in the middle of writing a script right now, and when I’m writing scripts, I’m consuming every bit of wisdom about the craft I can get my hands on, as if ingesting knowledge via as many senses as possible will somehow help this show get made.

I listen to Scriptnotes as I wash the dishes and go to the loo, I rake over Into the Woods and Philip Shelley’s newsletter like a spy looking for clues, I watch interviews with writers and directors convinced that listening to them talk about their process will magically improve my own.

The above interview was one of the good ones. Sorkin, of The West Wing, The Newsroom, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, A Few Good Men, and many more, talks about dialogue as music, his approach to character, admits his weakness (even lack of interest) in plot and explores his career in conversation with David Brooks. One of the questions I found most interesting - or revealing - for myself, was when Brooks asks:

‘Do you have a moral purpose [in your writing]? Are you trying to improve the world or are you trying to see the world?’

Sorkin doesn’t completely reply, but says he does not really have a political agenda. His doesn’t matter so much. It was the question that got me thinking: do I write to see the world, or improve it?

It begs a deeper question: do I think writing is my most effective way to improve the world?

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I love thinking about writing: as it pertains to activism, to memory, responsibility. I’m constantly looking for a why in writing, because at some deep level, I don’t know if I believe in the stories we tell about why it’s so important.

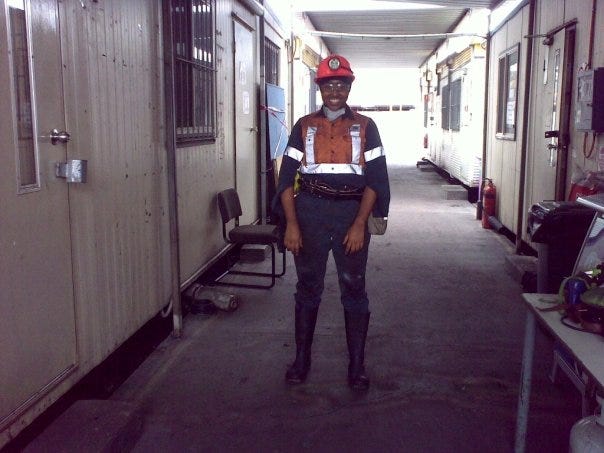

Engineers don’t spend all their time thinking about why they are engineers or why engineering is important. Training and working (and being raised by) engineers meant that I was always convinced of the importance of the profession, constantly evangalised it, spent my free time making it accessible for young people, low key made it my entire identity. Doctors, I feel, are similar - society, certainly the one I was socialised in, never questioned the importance of doctors. They were essential. Valuable. No question.

But writing feels like a fragile creature or delicate lace: constantly needing protection, reinforcement, justification for its existence. No-one, to my knowledge, has ever called a doily an ‘essential item’. Writers have always interrogated why they write, offering reasons, arguments, justifications.

Perhaps that is natural. To write is to think, and maybe if you’re a doctor or an engineer thinking about the why isn’t so much part of your job description. It doesn’t make you better at what you do, necessarily. Perhaps, thinking about the why in writing helps the work.

Does it?

Sigh. I’m not sure what the point of re-litigating this question even is. I mean, I’m writing, aren’t I? I’m doing the thing. Isn’t that enough? I’m not doing the engineering thing, even though it would make far more financial, societal and pscyhological sense. This truth about myself surprises me, often. Why don’t I return to engineering, I’m often asked, by myself and others. I’ll spin a tale of mostly-truths - I would need to retrain (not sure going back to drilling oil and gas is the finest idea), I would need to stop writing and having public opinions (the condition of every engineering company I’ve spoken to, and evidenced by the broken careers of many outspoken engineers who are often women and/or Black), I would likely go back to some version of a 9-5 (which I simply cannot abide).

I’ve thought about going ‘back’ constantly. I cannot tell you the number of times I have seriously considered re-applying for an engineering role, or a masters in some sort of engineering/tech related field. It has been an active question since I transitioned out, in 2017.

But the truth of the matter is far less rational. It’s uncomfortable, a wet swimsuit underneath a fresh outfit. The real, hard, ugly nub of the truth is, I just… don’t want to?

I feel embarrassed even typing it.

It feels far too flimsy a reason.

But then again, mama always said I never did anything I didn’t want to.

I loved engineering. I loved the way math and physics stretched my brain, I loved the satisfaction of solving hard problems, I loved being part of literally making the world work. I loved every bit of it. But, once I was booted out of daily life in industry, found new worlds of possibility in the arts, history, politics, the lure of my old life somewhat faded. That’s not to say it dissipated entirely, but contending with the reality of engineering versus my dream of it was difficult. I left the industry as those two stories began to diverge, pulling away like plastic film packaging over rotting fruit. But this feels disloyal to admit.

I wanted to change the narrative about women in STEM! I wanted to show how important it was to take up space! I wanted to beat the statistic that most women leave the industry within five years of graduating (I did not beat the stat). I was so committed to the story, I would rather bite into maggot inflected flesh with a rictus grin than change my tune. Frankly, I didn’t know how to.

I still don’t.

I don’t call myself an engineer anymore, because it is no longer what I do. I’ve now been a freelance creative for longer than I worked and studied in STEM. But I can’t seem to shake the belief that this work, the work of writing, the work of telling stories, is not essential.

Which begs an even deeper question: Why do I feel the need to be essential?

I think we’re getting to the truth of it now.

If you live in a world that tells you who you are is of no importance: whether because you are a woman, or African, or a migrant, or Muslim, there are a myriad of ways to respond. Maybe, mine was carved from my parent’s approach: become indispensable.

That way, you will never be taken out with the trash.

If you’re an engineer or a doctor, you will be needed. They might not like you, they might not stand you, and they certainly might try to make your life hell, but they will have to admit that you’re useful, and useful means valuable. Useful means alive.

If you’re not useful, then how will you protect yourself?

I don’t know if I will ever be free of the deep rooted need to be useful. It feels more visceral than rational, an embodied belief that I might not be able to ever change.

So, I live with this tension, and I wonder if it is a test from God. If I believe my worth is in being useful, yet I spend the majority of my time not being useful (according to my own rubric), what do I think of my own value?

I feel like Allah is asking me to sit with this question. To feel how it presses against my ego, the discomfort of a full bladder I refuse to relieve.

I have often felt Allah has drawn me to this path, but I’ve not understood why. The only reasons I could think of were laced with delusions of grandeur, that my writing might change things, do things, be useful.

But I wonder if actually, the path is more about me. About keeping me humble, keeping my ego in check. If what you do is not what you value, how might you need to change your metrics of what is valuable? Of who is valuable?

Maybe Allah is showing me that I had a fatal flaw in my value system. That I was placing value on human beings not for who they were, but what they did. That would need to change, if I truly wanted to live the abolitionist, transformational justice values I claim to hold.

Huh.

Looks like I write to see, and improve, eh? See the world, and improve myself.

Okay… back to that script, eh?

😅

See y’all next week, inshallah!

Yassmin

Your writing has helped me see Sudan in more humane ways. Your writing has helped me see how valuable women are to improving the STEM field to solve problems of climate change. Your writing has helped me see a clear way to combat racism. The world needs all these aspects of you, Yassmin!

This was so insightful. I read it as an IT-analyst by day writer by night, one who constantly berates myself for not writing full time.