One need never become a mother.

But to have a mother is to be finite.

To say "my mother" is to be mortal.

– Eugenie Brinkema

I was introduced to the Gilmore Girls by my half-Haitian Mormon friend on a warm Christmas day in a rural Australian town. This was my first ever ‘real’ Christmas; growing up in a Sudanese Muslim family the 25th of December was remarkable only for its ability to shut the doors of our local McDonald’s. My friend, the other Black person at the Youth Parliament camp I attended that winter break, had invited me to share the festive period with her family. Beset by curiosity and the wayward sense of adventure that characterised my late teens, I agreed.

My own family had little idea I was making this pilgrimage. All they knew was I was working a vacation job in a coal mine nine hours drive north of my hometown, Brisbane. It was 2008. In my state, coal jobs were the best jobs - the only jobs - for engineering students like me; hungry, ambitious, skint. The summer placement would cover my expenses for an entire year, and this promise of financial freedom, garnished with the argument it was ‘good for my CV’, was enough to convince my parents to let their seventeen-year-old hijabi daughter, who had never spent more than a few days away from home, move 500 miles away to work coal.

Parental permission secured, I informed my team at Youth Without Borders, the grass roots organisation I’d founded a year earlier, and the board of the Queensland Museum I had just joined, that I’d be out of town for a few months. I peppered my emails with text-based emojis, unable to hide my excitement. I would be working. How utterly grown up!

I was grown up, my mother reminded me. I was a professional. An adult woman, and the men in the mine would treat me as such. My mother’s advice was delivered in single kitchen bench conversation, the night before I set off. Her care was packaged in typical bluntness, as if I was being read my rights over tea.

Don’t wear tight trousers. Never let a man into your room. Only read educational non-fiction, leave that fantasy, childish stuff behind. Don’t be a show off, but remember to show your leadership skills. Don’t talk about yourself all the time. I am proud of you. Well done.

My mother confused me. In some ways, I was her mirror image. We had the same off-the-wall sense of humour, cared about the same causes, and looked so much alike that when we travelled back to Sudan, my aunts would mistake me for their sister. She was also my biggest believer. I would not have had the courage to start Youth Without Borders had it not been for her encouraging question: ‘If you want to, why not?’.

But my mother’s belief came with sky high expectations, floating out of reach any time I got close enough to touch. I found it unbearable, and she seemed unable to understand why. Mama only wanted what was best for me, didn’t I see that? Was that not a mother’s job?

So unlike Rory, the daughter in the show I was soon to become obsessed with, my life was not an open book. I shared scant details of my ever evolving life with my mother, not out of fear of a fire-and-brimstone style punishment, but out of a sapling’s barely conscious desire to bask in the warmth of a higher power. I wanted to be - or be seen as - good, in the eyes of my parents and in the eyes of my God, which at that point, was all but the same thing. I wanted to meet those atmospheric standards, be ‘good enough’, be the perfect daughter.

Rory was clever, witty, and knew her own mind. She ate her body weight in junk food, cared little for what others thought of her, was at ease with her ambitions and achieved them effortlessly. Most importantly, Rory was more than good enough for her mother. In Lorelai’s eyes, Rory could do no wrong. She was the perfect daughter.

But Brisbane was no Stars Hollow, and my mother had far more in common with Emily Gilmore than Lorelai.

I spent much of my adolescence and young adulthood desperate to be bathed in the light of my mother’s approval, committed to the asymptotic pursuit. But every so often, the embers of adventure would tempt me away from the pure light of her sun. My leaves would turn, compelled by tropism toward the open skies of the unknown.

I knew a ‘good’ Sudanese girl didn’t take three Greyhound buses by herself across the country to spend a week with a family her parents hadn’t vetted and approved. I knew a ‘good’ Sudanese girl would call her parents every night, diligently reporting who she had met and what she had done. I knew a ‘good’ Sudanese girl didn’t take a job in another town unless she was married, but that ship had long since sailed. While I was on my way to defining my own sense of being a Sudanese girl, I was holding onto the fiction that I could be both, what my mother wanted me to be and what I chose. The desire to break free, and the seeming impossibility of it. Where did that leave me?

Somehow, in the safe and wholesome world of the Gilmore Girls, I found characters grappling with similar questions.

At the time I visited in the late 2000s, Dalby, the land of the Baranggum First Nations People, was a town of under ten thousand inhabitants. According to the Gilmore Girls fandom wiki, that places the rural centre at roughly the same size as Stars Hollow. An agricultural hub, Dalby is well known for being the centre of a rich grain and cotton growing industry. It is far less known for its racial diversity. On arrival, we joked I had increased the Black population by 20%. Again, not too unlike Stars Hollow.

The journey to my friend’s place was fractious and confusing, featuring a missed bus connection, an awkward hostel stay in a twelve-bed room, a seven hour wait on Christmas morning at another bus depot and a nervousness that somehow, I was going to be caught out. But I made it, eventually, to the hot sweep of the Darling Downs, with its ocher fertile soil and verdant rolling hills. My friend’s home was a gorgeous two-storey house set back behind a forest of eucalyptus, standing guard like sentries. I don’t remember seeing any koalas on that trip, but I probably did, their grey fur camouflaged among the branches of dappled grey and white, laconic and drowsy. Queensland’s heat will do that to you, the baking heat rising from the earth slowing you down like molasses, nudging you towards shade, stillness, cool.

They had the tree, and the lights, and the food, and the crackers, and everything I imagined to expect from watching Love Actually. But my ignorance was on full display. I worried my tardiness meant I had missed the religious portion of the festivities, only to learn Mormons did not attend Christmas mass at all, the focus of the day being on family and togetherness. My lack of preparedness bit me at every turn: embarrassingly, I had not considered needing to bring a present for each member of the family, whereas they had all thought of me in their gift giving. My reasoning for keeping the Dalby adventure from my parents would soon morph from worry about their disapproval into shame at being such a poor houseguest. We trained you far better than this, my mother would scold, and she would be right.

But my hosts were generous, kind and gracious, welcoming my haphazard presence as its own blessing. And soon, in the cosy hours between Christmas lunch and Christmas dinner, when bellies are full and conversation slackens, my friend drew me into her room, patted a flat spot in the mess of her duvet, and invited me into a new universe.

We were only meant to watch the first episode, maybe the second. In the end, we had dinner in bed, balancing plates on our knees, the room darkening around us, our faces lit up by the flickering of the small TV. I don’t remember what time we went to sleep that night, I’m not sure I ever did. I kept wanting more, more, more of this world. They had so much to say, and it was all so funny, and genuine, and nice? The Gilmore dynamics felt familiar and foreign, all at once. I inhaled the show like I was taking my first full breath.

I had no template for the world of the Gilmore Girls. I knew nobody who was friends with their mother the way Rory was with Lorelai, had no conception of an adult who did not act like what I understood an adult to be. Here was a grown woman with a grown child whose relationship with her own mother still resembled my own. “Rory and I are best friends, Mom. We’re best friends first and mother and daughter second,” says Lorelai to Emily in episode sixteen of the second season, an admission so profound it threatened to breach my blood-brain barrier. What did that even mean? Wasn’t that unnatural? Yet, I watched on, unable to tell whether this was something I wanted, or decried, or both.

In the subsequent decade or so since the show aired (I do not consider the Netflix Original ‘A Year in the Life’ to be a valid part of the canon, we can argue about that in another anthology), I have pondered over what drew me in so securely to the world of the three generations of Gilmore Girls.

In 2016, Vox[1] published a piece positing the show’s popularity had something to do with its politics. “Running for almost the entirety of the Bush years, the show was an antidote to the conservative values that pervaded that era,” author Noah Gittell observed under the headline ‘Gilmore Girls’ subtle liberalism and universal empathy’. I began to watch the Girls the same year Lehman Brothers collapsed, smack bang in the middle of the United State’s War on the nebulous concept of ‘Terror’, so the argument would have credence, if not for the fact that 2008 was quite unlike much of the preceding decade. I came to the show soon after the resounding electoral defeat of Australia’s arch conservative Prime Minister John Howard, the same year Barack Obama was elected with the hopeful call of ‘Yes, We Can’. Indeed, I would wake up at 3am mere weeks after bingeing Gilmore Girls first three seasons to watch Obama’s historic inauguration speech inside my cabin, a few clicks outside the coal mine.

But Obama had never felt like my saviour, no United States President ever was. “Liberalism”, in the colloquial Western sense, had, throughout my teens, placed itself in opposition to my faith practice. White liberals obsessed with saving me from my headscarf were almost more annoying than white conservatives who surveilled my every teenage move for a sign I was a terrorist in disguise. At some level, I knew that if I had met Rory or Lorelai in person, they would not have folded me into their arms, welcoming me into the warm bosom of Luke’s diner with a smile and a sly shout for ‘more coffee!’. I was more likely to be a subject of their pity, a project to be worked on, a ‘teachable moment’. Did you know there is a genocide happening in Darfur? I could imagine Rory asking me, after the revelation I was born in Sudan, as if she was the first to bear this knowledge, the one to educate me about my own country. This rhetorical question would no doubt come hot on the heels of a comment Lorelai made about ‘exotic African countries’, or knowing about Sudan because she’d watched ‘The Last King of Scotland’ and wasn’t James McAvoy a total hunk and didn’t I think it funny a film about a Ugandan dictator had Scotland in the title and do you think Ugandans drink coffee? They really should get onto that because who doesn’t like coffee!

Given Uganda is one of the world’s top producers of coffee, it is likely that Lorelai was drinking Ugandan beans in Luke’s diner, but that only reinforces the point. I knew my real self would not have been a part of their world, in the same way I knew I was not actually part of the rural landscape of Dalby, nor the rough and tumble of the coal mine I had tried to claim my own. I was securely an outsider in Queensland, as in Stars Hollow. Yet somehow, I still felt of it. How?

“Gilmore Girls…foregrounds a class-based conflict, articulated as a generational tension between the show's two primary families, the senior Gilmores, Emily and Richard…and the ‘Gilmore girls,’ their daughter, Lorelai…and granddaughter, Rory…,” writes Daniela Mastrocola in Performing Class: Gilmore Girls and a Classless Neoliberal "Middle Class"[2].

Mastrocola critiques Lorelai’s ‘classless’ depiction in the series, which she argues reinforces the ‘ambiguous neoliberal notion of a middle class’. Was there something about this plucky, not-quite-working class dynamic I resonated with? A family obsessed with doing things on their own terms, who believed education was the route to social mobility, a woman (in Lorelai) forced into contradiction out of desire to provide for her daughter what she could not have for herself? I wondered if I saw something of my mother in both Emily and Lorelai, both the disciplinarian with sky high expectations, and the cheerleader with the belief her daughter is capable of anything, everything, so long as she put her mind to it. Alas, my attentions were not about the class dynamics, although Mastrocola’s piece on the ‘classless neoliberal middle class’ has much to commend it. This was about what Gilmore Girls is always about. The impossibility, the contradiction, the incurability of being daughter.

“Finitude is the daughter who will never catch up in time, in history, to the mother. The mother, the daughter - together these create a form of exchange, a form of the non approach to the origin, the impossibility of catching up fully (and to that which we most adore),” says Eugenie Brinkema (2012) in A Mother Is a Form of Time: "Gilmore Girls" and the Elasticity of In-Finitude[3]. The show is, “in the end, a series about what it means to be a little too close, about the problem of boundaries and the impossibility sometimes with family, with texts, and with television of knowing where one structure ends and the other starts.”

Where did I begin and my mother end? At the tender age of seventeen, I wasn’t sure, but I was downright afraid of knowing the answer. I was a high achieving young woman, but there was a part of me that feared any success I enjoyed was my mothers, any failure I befell my own. I had founded a youth organisation, joined boards and been nominated for awards, but was that my own doing, or was I mere cipher for my mother’s ambitions? I had been commended for my activism and my voice, but was that my doing, or the opportunities my mother had hustled for, magicked out of thin air, a visionary without the resources to build her dreams beyond the weak seedling she had birthed?

Where did my mother end and I begin? She was the ‘good’ Sudanese woman, one who would have never taken the bus trip I did, never used a cuss word I enjoyed curling my tongue around, never have dreamed of ending up with a neck-tattooed coal miner, as I had done in the cool darkness of my cabin, time and time again. As I aged, I would learn of all my mother did that placed her outside the bands of ‘goodness’ in the eyes of other Sudanese women. But for me, anything she did must be good, for she was mother.

What was ‘Mother’ but ‘Good’, and if Mother was Good, what did that make me? Was daughter the extension of mother, or its opposite, its reflection, its contradiction?

If Mother is Good, where do we allow for Mother to be human?

Perhaps that is what made Gilmore Girls so compelling for me, all those years ago. Perhaps that is what remains potent, despite its politics, its whiteness, its unreality. The real shine of Gilmore Girls was less what it told me about myself, and more what it showed me of my mother. After all, while motherhood might be temporal, every mother is a daughter, and daughter is a permanent state.

I met my friend again recently, thousands of miles away from Dalby, with many Christmases now under my belt. We were older now, wiser, with our own questions about being mothers ourselves, although neither of us had yet to pass that threshold. Partway through the conversation, I mentioned I was writing this essay, my eyes full of nostalgia, hiding a shy request for permission I was not sure I needed.

Her sad laugh shocked me. ‘Gilmore Girls was my depression show,’ she said, her mouth twisting with the admission. I choked on my water, unable to match her words with my recollection. ‘Really?’ was all I could manage.

How could I not have seen it at the time? The hours we spent sharing her duvet, watching episode after episode of a fictional world where there are solutions to every challenge and the problem is never your brain chemistry or your metabolism. I thought of us watching the first season’s Christmas episode while real-life Christmas swirled around us. The festive season had felt like a performance, but aren’t we all always performing? Performing daughterhood, performing womanhood, performing goodness, performing self. While some might critique the performance as separate from reality, perhaps what Gilmore Girls taught me was performance, ‘surficiality’, in the words of Eugenie Brinkema, is a ‘pure plane of being’.

Brinkema insists on the ‘value of the surface’, claiming it ‘is not a plane to be broken, that richer treasures underneath might be mined, pillaged, and plundered, but that gloss, speed, sensation, and distance are themselves worthy of theoretical insight and time.’

My friend’s performance of wellness, my own performance of adventure, my mother’s performance of contentment, the Girls performance of it all. The surface, the performance, reality, worthy, in its own right. Therein lies the contradiction, and the beauty; the latter being the former, the former performing the latter, akin to a real life Mobius Strip.

Contradiction, and beauty. One a mother, one a daughter, the two both and neither, one and the same, wrapped up in infinitude.

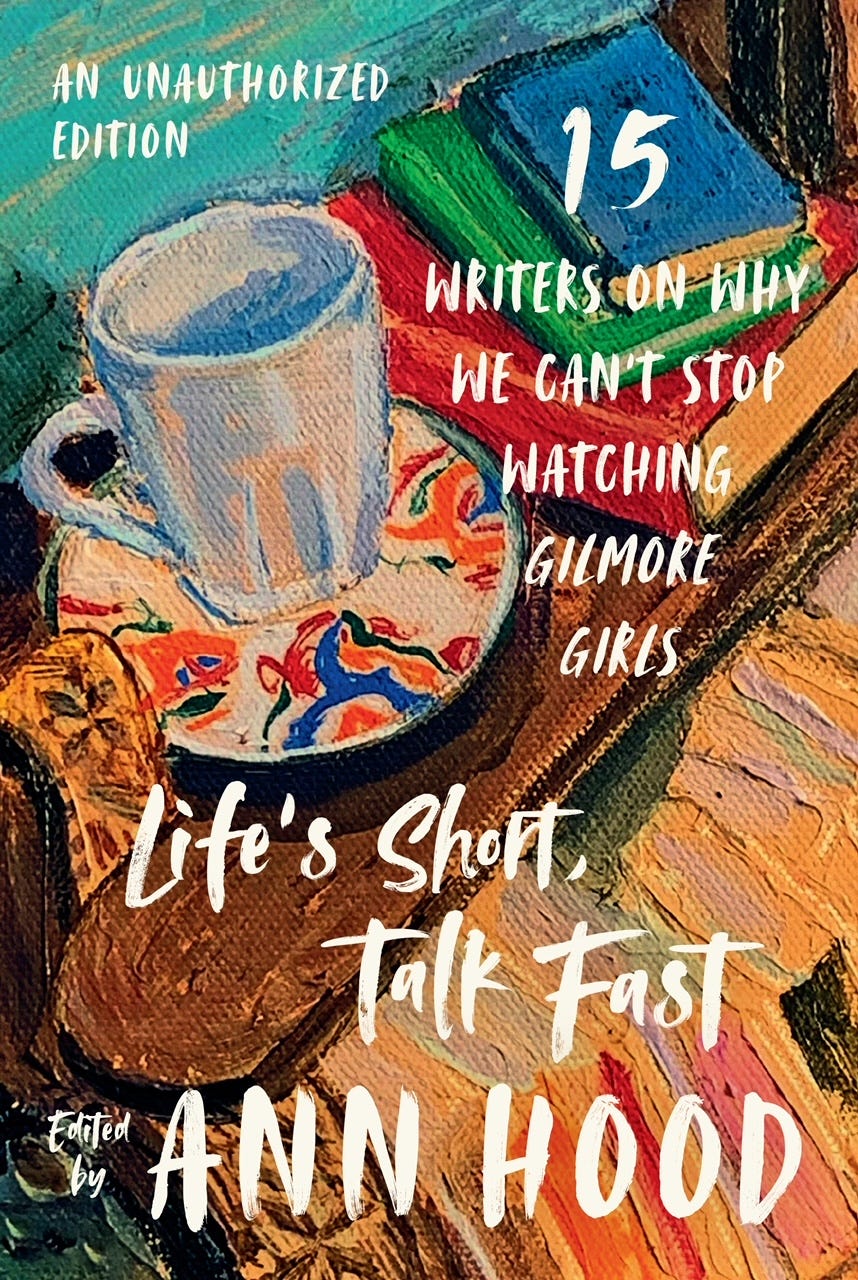

This is an excerpt from an anthology I contributed to, all about the Gilmore Girls, titled: Life's Short, Talk Fast: 15 Writers on Why We Can’t Stop Watching Gilmore Girls. It was published in November 2024, and is still available for purchase! I definitely recommend you check it out.

Tell me - did you ever watch The Gilmore Girls? What was your relationship with the show, or its characters? I look forward to hearing your thoughts!

[1]https://www.vox.com/culture/2016/11/22/13653760/gilmore-girls-liberal-politics-conservative-era

[2] Mastrocola, D, (2017) Performing Class: "Gilmore Girls" and a Classless Neoliberal "Middle Class", Studies in Popular Culture , SPRING 2017, Vol. 39, No. 2 (SPRING 2017), pp. 1-22, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44779928

[3] Brinkema, E. (2012). A Mother Is a Form of Time: “Gilmore Girls” and the Elasticity of In-Finitude. Discourse, 34(1), 3–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41850967

I had to scroll back to double check that if you’d in fact founded an organisation and were on the board of a museum at 17!! I so enjoy your writing! I was obsessed with the relationship between Lorelai and Rory when I was a pre-teen because my own relationship with my mother was so fraught with tension and resentment. Thank you for writing this beautiful piece!

I really loved this essay, thanks, Yassmin. I've thought a lot about this - mothers and daughters - but you articulate it better than I've ever managed to in my own thoughts. I was similarly fascinated with the Gilmore Girls but like your friend, it was a depression watch for me, too. Thanks for writing and sharing this - I feel this is an essay I will revisit, and will definitely look at the anthology.