A Writer's Responsibility

What does it mean to 'do language' in times of crisis?

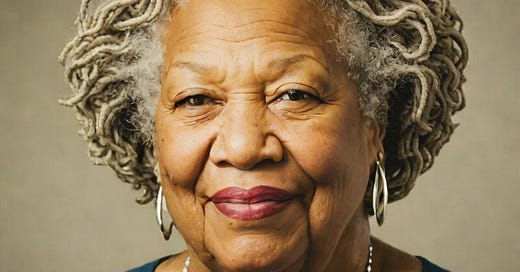

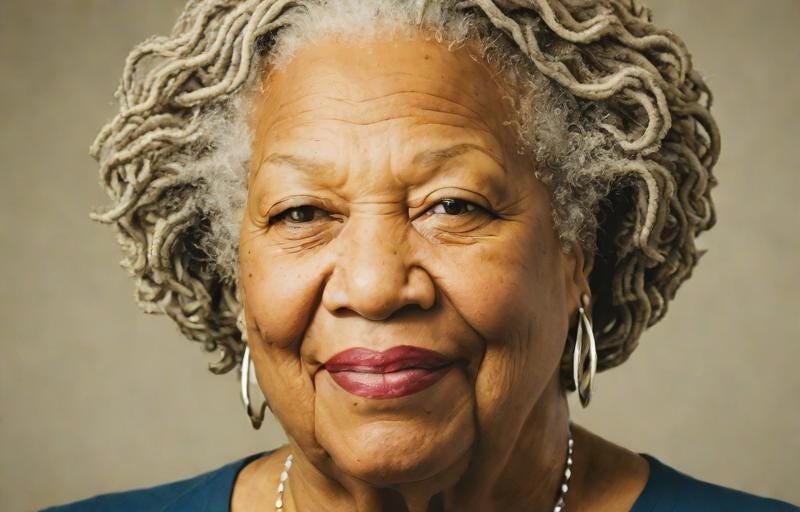

There’s a Toni Morrison quote I’ve seen making the rounds, about the power of language, particularly during times of crisis.

‘This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.’

The quote comes from a piece Morrison wrote for The Nation in 2015, and one can’t help but wonder what the Black American literary giant might have made of the role of the writer today.

It’s a plausible position, to be sure. It feels powerful, compelling, urgent. But I’ll be honest with you here - I’ve never felt fully convinced.

I have not been sure why I found this position, the deep reverence for the role of the artist in the face of oppression, so uncomfortable. To be honest, I’ve often just quitely accepted that perhaps I was wrong, there was something I was missing. So many wonderful artists have said similar things, surely they know something I don’t.

It was not until I read this fantastic essay by Indian writer and political thinker Pankaj Mishra that the penny dropped (unpaywalled here).

…bravery and cowardice have too often subsumed the complexity of writers’ experiences in popular tyrannies. Writers who fled or were expelled from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe during the cold war, for example, helped create an image in the so-called free world of the fearless “dissident”—the writer who speaks truth to power (as if power doesn’t already know the truth).

In recent years storytelling has been widely upheld as axiomatically opposed to despotism and demagoguery—as though despots and demagogues were not seductive storytellers themselves, with arguably greater influence. (emphasis mine)

Storytelling in of itself cannot be enough. As Mishra points out, despots and demagogues, bigots and Borises, are all persuasive, compelling storytellers. Part of why right wing movements are sweeping the Global North is due to their leader’s abilities to spin great narratives. Doing language in of itself is not enough. Language must be underpinned by a greater moral purpose, anchored to values such as justice and accountability, lest it be co-opted, warped, transfigured into weaponry able to be used against the very people it intended to defend.

Mishra also punctures the idea that writers are somehow better placed than others to not only ‘do language’, but act as paragons of virtue, leaders not by virtue of their virtue, but by their dexterity with the written world. Such a position comes from privilege that many around the world, and throughout history, do not enjoy. He writes:

Such (over)estimations of writerly wisdom and power seem to come easily to observers in the United States and Britain, two of the most powerful and stable societies in the modern era, where most writers have never found themselves at the desolate conjuncture Wittstock describes. It has been the grievous fate of writers elsewhere in the last century—in Germany, Spain, Russia, and the countries of Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa—to grapple with some fundamentally unanswerable questions: When to leave, for where, and with what guarantees of a stable or dignified exile? (emphasis mine)

Where to go? That is the question, one of the many. Where to go, and when, and why leave at all? What is stable and dignified exile, in this day and age? As someone who left their home, twice - once at the behest of my parents, once under my own violition - I am intimately familiar with the tragedy of the choice, of the profound and utter isolation of exile, self-imposed or otherwise. Is it a solution? For the individual, yes. It certainly was for me, and has been for artistic friends of mine from Sudan, and Russia and countries beyond. But, and this is the question I sometimes grapple with: if we all leave, who is left to fight?

I suppose what I am trying to do is arrive at a clear understanding of my ‘job’ in this moment. How can I be most effective in a time where tragedy and crisis rage around us, a constant and unceasing firestorm we can barely shield our own bodies from, let alone others? At times, it feels like the only salve is to bury not only our heads in the sand but our whole bodies, creating underground bunkers that cocoon us from the scalding heat of the outside world. But life is not meant to be spent sequestered away, hidden away from the sun. Are words enough to make a difference? Is language enough to safe life?

The answer, of course, is everything. Yes, and no, and Yassmin, you know that is the wrong question to ask. What I am trying, and failing to do, is optimise the process of revolution, the transformative change towards justice I so deeply yearn for. I am applying a problem-solving, engineering mindset geared towards the complicated challenge (we have the tools to arrive at solutions, we just need to design the process) rather than grounding myself in the complex (we don’t know how to fix this, we will just iterate until we ge there).

Facing the complexity means accepting one’s lack of control. Facing the complexity forces us - me - into holding onto nothing more than faith. Faith that things will work out, faith that our efforts will amount to something, faith that things will get better, can get better, must get better.

Doing language, to me, is an act of faith. Perhaps Auntie Toni was onto something, after all.

Read: Memory Failure

Another powerful essay by Pankaj Mishra, whose work I cannot recommend highly enough. This explore’s Germany’s failure to recognise its role in facilitating Israel’s war crimes, now and over the years.

The only European society that tried to learn from its vicious past is clearly struggling to remember its main lesson. German politicians and opinion-makers are not only failing to meet their national responsibility to Israel by extending unconditional solidarity to Netanyahu, Smotrich, Gallant and Ben Gvir. As völkisch-authoritarian racism surges at home, the German authorities risk failing in their responsibility to the rest of the world: never again to become complicit in murderous ethnonationalism.

Watch: The Gentlemen

This is an utterly escapist Guy Ritchie show, less about doing language and more about a reprieve from the firestorm. On Netflix.

Honourable mention to this episode of John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight (watch with US VPN) on a phenomenon called ‘Pig Butchering’, which is far less bloody but just as tragic, as you’d imagine.

Listen: Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Lecture

The fact we have such wisdom accessible to us at the click of a button never fails to astonish me. Toni Morrison’s Nobel Lecture is far more eloquent about the ‘doing of Language’ than a short newsletter from me will ever hope to be, so do take the time to have a listen. Access the transcript here.

Thanks, everyone, for your support of this newsletter. I love reading your comments, seeing your engagement, having the conversations after the fact. I also want to shout of Janet for signing on as a FOUNDING MEMBER, which was such a gift to me on a difficult day.

I always appreciate a sign up (I see every single one!) and a subscription upgrade. But I know life is hard right now, so don’t feel any pressure. I write this newsletter because I want to, not because I have to, and I feel so grateful for all your energy and attention.

If you want to read a little more of my work, my interview with Fatima Ahmed in Cycling Weekly came out this week, as did an excerpt of one of my favourite essays from Talking About A Revolution, in Sheffield Magazine, Now Then.

Until next week,

Yassmin

I love this style of writing Yassmin, the critique, the questioning, the exploration and with no intention to round it off with a pretty bow, it feels like a question that I’m taking with me, into my world, about what my role with words is, if I’m fulfilling it, and if it even makes any difference anyway. From a self-indulgent perspective, if I FEEL my words; that is my guide on what and how to write. I also acknowledge the deep privilege I have to even experiment here with my art.

Thank you for this rich essay!

Everybody has their tool, and some have numbers of them - so isn't it that we use the ones we have? Writers do language and some tell stories because that is the way they are most effective. Others orate on a stage. Of course, yes, demagogues are great storytellers, but doesn't that mean it's even more important for those who seek a higher truth, who question deeply and who want to reveal and lead others to a more just world to tell a different story? Some will write stories of justice, some will spruik them, some will act them out. We need them all, in every medium, and especially in the enduring medium of writing, as many as we can gather together, to counter and replace the seductive stories of bigots and Borises.